Interest Rate Swaps, Volume 1

Download a PDF of this white paper

Overview

Interest rate swaps are commonly used for a variety of purposes by a broad number of end users. Users can range from small borrowers that desire to fix the rate on their variable rate loans, to institutional investors that want to manage the duration of their assets without trading the assets themselves, to hedge funds that speculate on the direction of interest rates. This volume is designed to outline the basic mechanics, benefits, risks, uses, pricing, and valuation of interest rate swaps. Basis swaps have been excluded as they will be covered in another volume.

Mechanics: Pay Fixed Swaps

The examples below are designed to outline the mechanics of specific uses for interest rate swaps under which an end user pays fixed and receives variable. These examples are by no means intended to be an exhaustive list of potential uses.

Hedging Variable Rate Debt

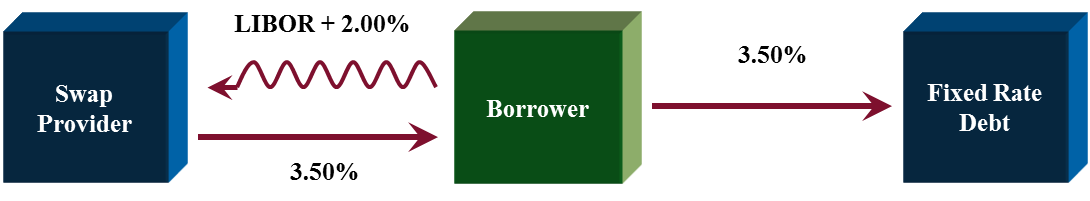

One of the more common uses of interest rate swaps is converting variable rate debt (such as a bank loan) to a fixed rate. As outlined in Figure 1 below, the borrower pays a variable rate on its debt – plus a spread – for a specified period of time. This variable rate can be based upon numerous indices such as LIBOR, T-Bills, PRIME, or a tax-exempt index such as SIFMA. For the purposes of this volume, we have assumed LIBOR.

Under the swap, the borrower i) receives a variable rate equal to the rate it pays on its debt and ii) pays a fixed rate determined by market conditions on the day of pricing. The variable rate that the borrower receives on the swap offsets the variable rate it pays on the debt leaving it with a payment based on a fixed rate of interest.

Mechanically, the fixed and floating payments on the swap are typically netted against one another. These payments are referred to as ongoing settlements. In addition to ongoing settlements, end users should concern themselves with the market value of the swap. The market value is what the borrower would pay or receive if it were to terminate its swap prior to the stated maturity. These valuations will be discussed in more detail later in this volume.

Figure 1: Pay Fixed Swap Mechanics

Forward Hedging Fixed Rate or Variable Rate Debt

Borrowers that know they will need to borrow funds in the future – but are concerned about rising interest rates today – can lock their cost of funds in advance by using a forward interest rate swap.

For variable rate debt, a borrower would enter into a swap similar to that outlined in Figure 1 to begin in the future. On or near the future start date of the swap, the borrower would obtain the variable rate debt and leave the swap in place.

For fixed rate debt, a borrower would enter into a swap similar to that outlined in Figure 1 to begin in the future. However, on or near the future start date of the swap, the borrower would obtain the fixed rate debt and concurrently terminate the swap. In a rising rate environment, the borrower would owe a higher fixed rate on its debt, but would expect to receive a payment upon terminating the swap. The payment received from terminating the swap – if structured correctly – decreases the amount borrowed and thus preserves the originally anticipated debt service payments. Conversely, in a falling rate environment, the borrower owes a lower fixed rate on its debt, but would expect to owe a payment upon terminating the swap. The size of the debt is increased to account for the swap termination and the debt service is again preserved.

Converting a Fixed Rate Asset to a Variable Rate

The exact same swap can be used by an investor to convert a fixed rate asset to a variable return. As outlined in Figure 2 below, the investor receives a fixed rate on its asset for a specified period of time. Under the swap, the investor i) pays a fixed rate equal to the rate it receives on its asset and ii) receives a variable rate determined by market conditions on the day of pricing. The fixed rate that the borrower receives on the asset offsets the fixed rate it pays on the swap leaving it with a return based on a variable rate of interest – plus a spread.

Figure 2: Pay Fixed Swap Mechanics

Mechanics: Receive Fixed Swaps

The examples below are designed to outline the mechanics of specific uses for interest rate swaps under which an end user receives fixed and pays variable. These examples are by no means intended to be an exhaustive list of potential uses.

Converting a Variable Rate Asset to a Fixed Rate

As outlined in Figure 3 below, the investor receives a variable rate on its assets. This rate can be based on several indices such as 30 day T-Bills, tax-exempt money market rates, or LIBOR. For these purposes, we have assumed LIBOR plus a spread. Under the swap, the investor i) pays a variable rate equal to the rate it receives on its assets and ii) receives a fixed rate determined by market conditions on the day of pricing. The variable rate that the investor receives on the asset offsets the variable rate it pays on the swap leaving it with a return based on a fixed rate of interest.

Figure 3: Receive Fixed Swap Mechanics

Forward Hedging Fixed Rate or Variable Rate Assets

Investors that know they will need to purchase assets in the future – but are concerned about falling interest rates today – can lock their return in advance by using a forward interest rate swap.

For variable rate assets, an investor would enter into a swap similar to that outlined in Figure 3 to begin in the future. On or near the future start date of the swap, the investor would purchase the variable rate assets and leave the swap in place.

For fixed rate assets, an investor would enter into a swap similar to that outlined in Figure 3 to begin in the future. However, on or near the future start date of the swap, the investor would purchase the fixed rate asset and concurrently terminate the swap. In a falling rate environment, the asset would become more expensive, but the investor would expect to receive a payment upon terminating the swap. The payment received from terminating the swap – if structured correctly – would allow the investor to upsize its purchase and thus preserves the originally anticipated investment yield. Conversely, in a rising rate environment, the fixed rate asset would become cheaper, but the investor would expect to owe a payment upon terminating the swap. The payment owed on the swap would downsize the asset purchase and the investment yield is again preserved.

Converting Fixed Rate Debt to a Variable Rate

The exact same swap can be used by a borrower to convert fixed rate debt to a variable rate. As outlined in Figure 4 below, the borrower pays a fixed rate on its debt for a specified period of time. Under the swap, the borrower i) receives a fixed rate equal to the rate it pays on its debt and ii) pays a variable rate determined by market conditions on the day of pricing. The fixed rate that the borrower receives on the swap offsets the fixed rate it pays on the debt leaving it with a payment based on a variable rate of interest – plus a spread.

Figure 4: Receive Fixed Swap Mechanics

Benefits

Many infrequent end users are not fully aware of the benefits of interest rate swaps. The benefits outlined below are specific to those end users that hedge interest rates on debt. In general, these benefits also apply to end users that hedge interest rates on assets.

Structuring Flexibility

Term: Interest rate swaps can be used to hedge a portion of a borrower’s debt for a term less than the debt’s maturity. This allows borrowers to micro manage their interest rate risk as rates fluctuate over time without altering the underlying debt. As rates decrease, borrowers can hedge additional portions of their debt up to a maximum of 100%. As rates increase, borrowers can terminate portions of their swaps down to a minimum of 0%. This method of debt management is similar to dollar cost averaging in asset management. The liquidity of the interest rate swap markets makes this style of management very efficient.

Structure: Borrowers can structure swaps so that the coupon increases or decreases over time. This can be useful when the underlying financed asset in known to produce more or less income over time. Amortization can be added to interest rate swaps to match the amortization of the underlying debt or to amortize at a faster rate and thus decreasing a borrower’s fixed/floating mix over time. Call features can be added to interest rate swaps to i) give borrowers the right to terminate the swap at par (or some agreed upon amount) in the future or ii) give borrowers a lower coupon by selling their swap provider the right to cancel the swap at par (or some agreed upon amount) in the future.

2-Way Prepayment

Unlike traditional fixed rate debt instruments, interest rate swaps may be terminated voluntarily for a gain. Once the fixed rate for a swap has been established, the swap will have either a positive or negative value (commonly referred to as “mark-to- market”). For fixed payer swaps, the fixed rate payer will have a positive mark-to- market when comparable fixed rates are above the fixed coupon on the swap. For fixed receiver swaps, the fixed rate receiver will have a positive mark-to-market when comparable fixed rates are below the fixed coupon on the swap.

Liquidity

The total notional of the global Over the Counter (“OTC”) derivatives market as of June 2013 was approximately $693 trillion [1]. Of this amount, interest rate derivatives are the largest segment at approximately $577 trillion. Because of the size and scope of the interest rate derivatives market, the bid-offer spread on these contracts (excluding charges for credit risk) is extremely small. This means that end users can easily enter and exit the market for nominal costs. Note: This assumes that end users have the ability to price OTC derivatives or have advisors that assist them in pricing. OTC derivatives are complex instruments to price and many end users are unaware of what spread they’re ultimately paying.

[1] Bank for International Settlements. “OTC derivatives market activity in the first half of 2013” http://www.bis.org/publ/otc_hy1311.htm.

Independent OTC Contracts

Interest rate swaps are independent from the underlying debt (or assets) that they are intended to hedge. They are governed by a separate set of documents maintained by the global trade association International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. (“ISDA”). This independence allows end users to transfer interest rate swaps from one piece of debt to another. Additionally, because interest rate swaps are OTC contracts they can be traded from one swap provider to another.

Risks

As with any financial contract, there are certain risks associated with interest rate swaps. The list below represents the most common risks.

Termination Risk

If an interest rate swap is structured properly, end users should have the right to voluntarily terminate the swap at their discretion. However, there are certain provisions – Termination Events, Events of Default – within the ISDAs that may force an end user to terminate earlier than they may desire. If these events are triggered and the mark-to-market of the contract is a liability to an end user, they will be required to make a termination payment that they otherwise did not expect to make.

Counterparty Risk

If a swap provider defaults on its obligation under an interest rate swap or no longer participates in the swap market (i.e. – Lehman Brothers), the end user may be required to terminate the swap or assign it to another swap provider at a higher rate and/or with a lower credit rating.

Collateral Posting and Margin Calls

Since the implementation of Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, many end users are required to “clear” their swaps on an exchange. Simply put, these end users must post sufficient collateral on a daily basis to support the mark-to-market value. Additionally, many non-cleared swaps require end users to post collateral on a regular basis. Regardless of whether swaps are cleared or not, large daily swings in interest rates may put significant financial strain on end users that are not well capitalized.

Basis Risk

To the extent a swap does not perfectly offset the risk intended to be hedged, an end user is exposed to basis risk. This is commonly seen in the municipal marketplace where borrowers will issue Variable Rate Demand Bonds (“VRDBs”) and then hedge their risk with a swap based on either the SIFMA index or a percentage of LIBOR. Because the rate on the VRDBs is determined by investor demand for that particular borrower’s credit, a SIFMA based swap and LIBOR based swap will leave the borrower exposed to some amount of basis risk. Fixed rate borrowers can experience the same type of risk using swaps to “forward hedge” a fixed rate debt issue where pricing is based upon U.S. Treasuries.

How are Swaps Priced and Valued?

In its simplest form, an interest rate swap is a series of two cashflows: one that the end user will pay and one that the end user will receive. For the purposes of this analysis, we will examine a pay fixed swap that hedges an end user’s $10 million, 10 year variable rate term loan.

Pricing Swaps

Figure 5 below illustrates (i) a sample forward curve used to estimate the floating rate receipts over the life of the swap and (ii) a fixed rate used to determine fixed rate payments over the life of the swap. In this case, the present value2 of all the estimated floating payments equals the present value of all the fixed payments. This is known as the “mid-market” 10 year fixed swap rate. In this example, the borrower who is paying fixed and receiving variable is expected to pay more than they will receive for the first 3.5 years and then receive more than they will pay for the last 6.5 years of the swap. On a present value basis, the total of these positive and negative cashflows is $0.

Figure 5: Sample Fixed vs. Float Curves

Valuing Swaps

Each swap, regardless of its terms – maturity, amortization, day-count, index, size – has a unique mid-market rate. Providers of swaps – typically banks – will add a spread to the mid-market rate to cover various costs including credit risk and profit. Once a swap rate is locked, it will carry a positive or negative value depending on the direction of interest rates. That value is based on the amount by which swap rates have moved since inception plus any spread a swap provider has added. For a borrower paying fixed and receiving variable, an increase in rates will move the value of a swap in their favor. A decrease in rates will move the value of a swap against them. Because the calculation is based on the present value over the life of the swap, small movements in rates can have big impacts on the value of long-dated swaps. The table below [3] shows hypothetical values of a $10 million, 10 year swap over time in a higher rate environment.

[3] These numbers are estimates based on a parallel shift in the yield curve. "In the Money" values imply that the Replacement Rate is above the Borrower's swap rate. "Out of the Money Values" imply that the Replacement Rate is below the Borrower's swap rate. The Replacement Rate is represented by a swap with terms identical to that of the Borrower's then-remaining swap contract.

The table below [4] shows hypothetical values of a $10 million, 10 year swap over time in a lower rate environment. You’ll note that the absolute value of the swap is higher in a lower rate environment (e.g. – 100 bps out of the money) than it is in a higher rate environment (e.g. – 100 bps in the money). This is known as convexity and is due to the fact that cashflows are smaller when discounted at a higher rate.

[4] These numbers are estimates based on a parallel shift in the yield curve. "In the Money" values imply that the Replacement Rate is above the Borrower's swap rate. "Out of the Money Values" imply that the Replacement Rate is below the Borrower's swap rate. The Replacement Rate is represented by a swap with terms identical to that of the Borrower's then-remaining swap contract.

Summary

Interest rate swaps are common tools used by many borrowers and investors to change the makeup of their interest rate risk profiles. An end user can enter into a pay fixed/receive variable swap or receive fixed/pay variable swap depending upon their desired outcome.

Investors can:

Use pay fixed swaps to convert fixed rate assets to variable

Use receive fixed swaps to convert variable rate assets to fixed

Borrowers can:

Use pay fixed swaps to convert variable rate debt to fixed

Use receive fixed swaps to convert fixed rate debt to variable

By discounting both forecasted variable rate cashflows and fixed rate cashflows over the term of the swap, an end user can calculate a swap rate at inception and monitor its value throughout its life. This value will be carried on an end user’s balance sheet as an asset or a liability depending upon the purpose of the swap and the absolute level of interest rates at any given time.

End users that anticipate using interest rate swaps as a risk management tool should fully understand the mechanics, benefits, and risk of interest rate swaps and consider hiring a swap consultant that is well versed in structuring, pricing, documenting, and executing these opaque products.